Autor: Carlos Contreras

With inflation running at rates not seen for decades, the distortions it creates in the tax burden of households in a progressive and not fully indexed personal income tax need to be reconsidered. However, some politicians love inflation because it not only contributes to lower public debt ratios by increasing nominal GDP (in the dividend ratio), but can also increase tax revenues (in the divisor). Inflation is an «invisible» tax with a low «political cost» as it does not require legislative approval.

How inflation distorts personal income tax?

Musgrave defined tax neutrality with respect to price inflation as a situation where inflation affects neither the level of real revenues nor the distribution of the tax burden across (real) income groups. Many tax systems are not neutral with respect to changes in the general price index. The Spanish tax system is a case in point. In the case of personal income tax, inflation can distort the tax burden in several ways:

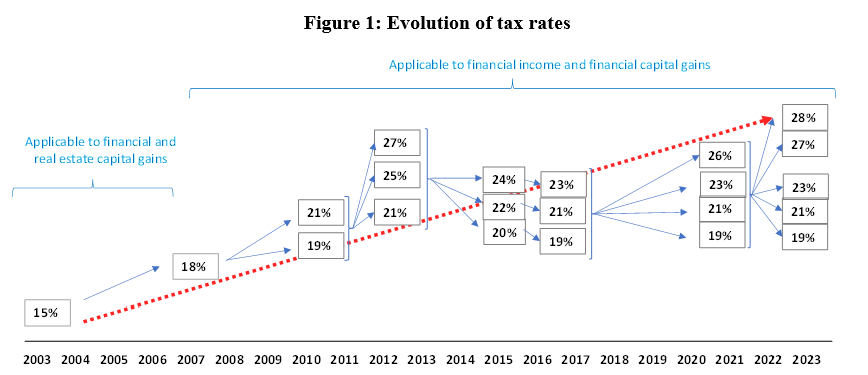

On the one hand, inflation erodes the value of exemptions and deductions in nominal euro terms, leading to an increase in the effective tax rate. On the other hand, inflation creates a cold progression. When brackets are fixed in nominal terms, inflation pushes taxpayers into progressively higher brackets. In Spain, it is not only income from sources such as labour and property that is subject to progressive rates. In 2010, our tax system changed from a flat rate to a progressive rate for capital income and capital gains. In addition, the number of brackets has been increased over time from two to five, and the rates applicable to the higher brackets have been raised to 28%. See Figure 1.

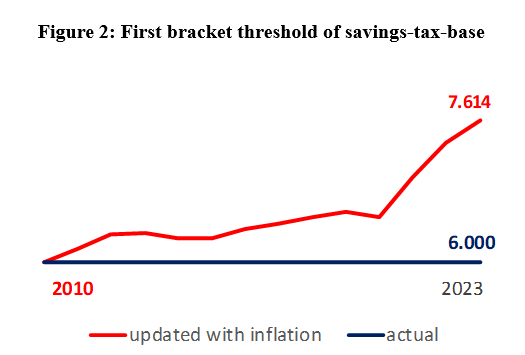

Despite inflation, the threshold for the first capital gains tax bracket has remained stagnant at 6,000 euros since 2010. In order to avoid a bracket jump (which currently increases the tax rate by 2 percentage points), this threshold should have reached €7,614 in 2023. See Figure 2.

Finally, the erosion of purchasing power makes the size of nominal capital gains at least partly illusory. Only real capital gains should be taxed. We focus on this particular point.

How to mitigate taxing nominal capital gains

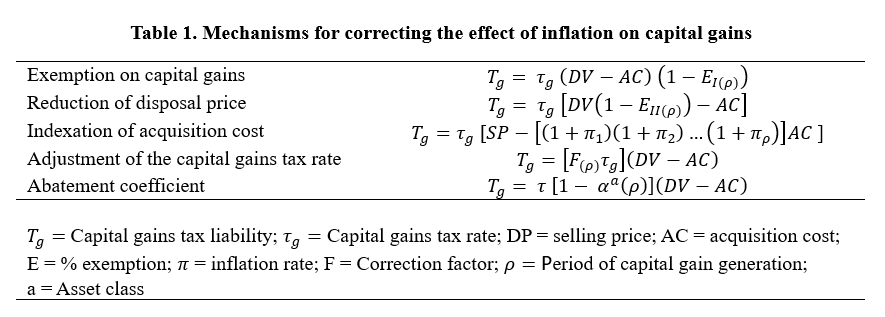

Various mechanisms have been put in place to avoid income taxation of purely nominal capital gains. These systems include the establishment of

- Exemptions on realised capital gains.

- Reductions in the sale value used to calculate the tax base.

- Indexation of acquisition costs according to the evolution of the consumer price index.

- Adjustment of the applicable tax rate on capital gains according to the impact of inflation.

- Reductions in the tax base based on the length of time the asset has remained in the taxpayer’s portfolio.

Table 1 gives an overview of common formulas for these mitigating mechanisms.

Although all the mechanisms described above have been applied in Spain at different times, recent tax reforms have meant the de facto removal of taxpayers’ protection against inflation. This has created a clear tax disincentive to save.

Measuring the impact of inflation on capital gains taxation

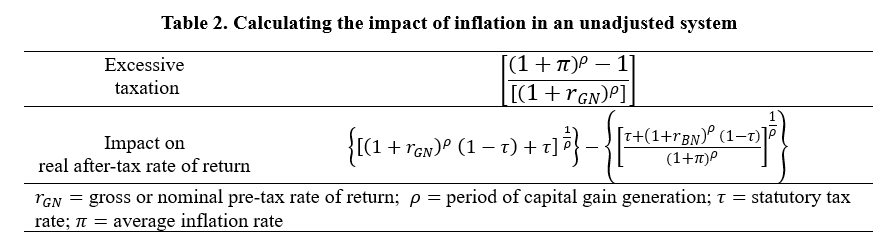

The distortionary effect of inflation on the capital gains tax burden (in the absence of corrective mechanisms) can be assessed in two ways:

- Excessive taxation (proportional increase in tax liability).

- Negative impact on the real after-tax rate of return.

The calculation formulae are shown in Table 2.

Numerical example

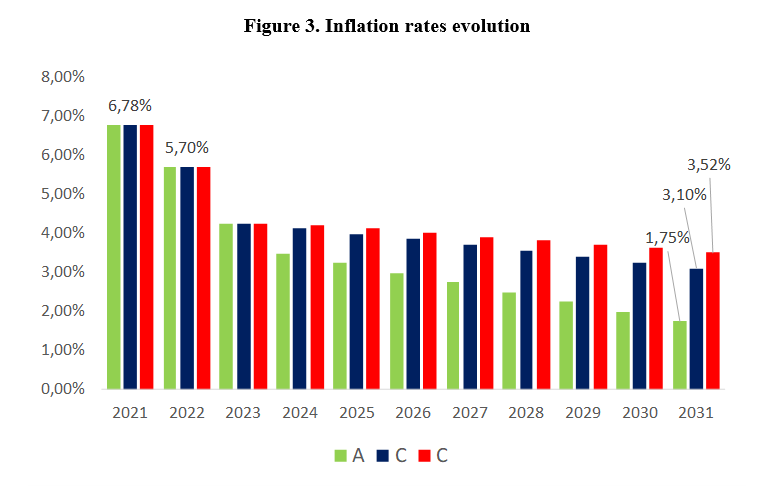

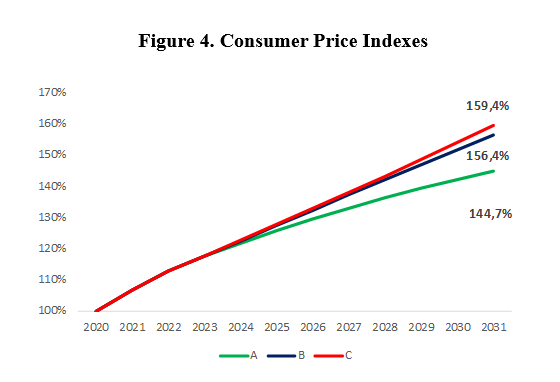

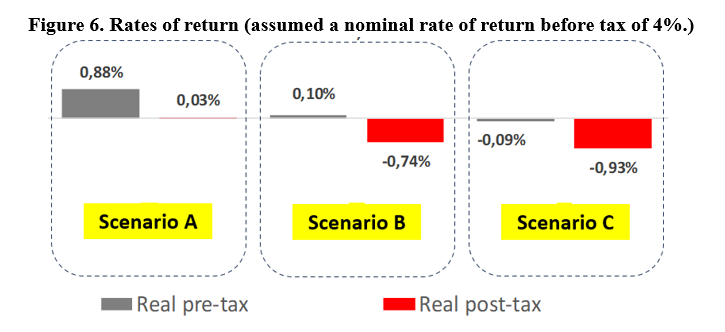

Let’s consider an asset invested over the period 2021-2031 at a known nominal pre-tax rate of return of 4.00%. The assumed statutory tax rate is 25%. There is no inflation adjustment mechanism. Let us consider 3 inflation scenarios (A, B and C) in which there continues to be a gradual decline in interest rates. See Figure 3. According to these scenarios, the trajectories of the CPIs at the end of the period are consistent with average inflation rates of 3.09%, 3.89% and 4.09% respectively. See Figure 4.

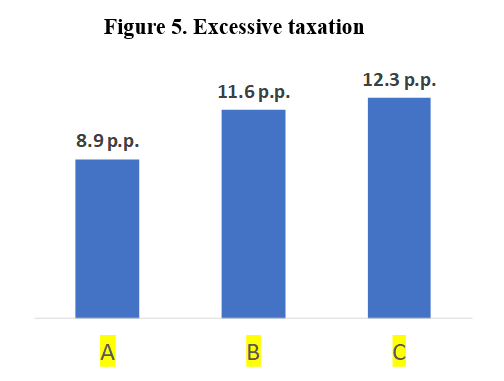

The estimated excess tax liability, which increases with the average inflation rate, ranges from 8.9 to 12.3 percentage points. See Figure 5.

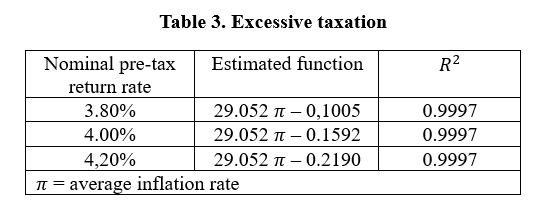

The sensitivity of the estimated functions determining excessive taxation for three nominal pre-tax rates of return is shown in Table 3.

Due to the excessive taxation resulting from the lack of adjustments, real after-tax returns are even negative in scenarios B (-0.74%) and C (-0.93%) of inflation. See Figure 6.

Consequently, it can be argued that the tax disincentive to financial saving for individuals is currently evident in a context of inflation in Spain. A reform of the personal income tax is therefore urgently needed to prevent the continued penalisation of saving.

Carlos Contreras: Licenciado y Doctor en Economía (UCM) y M.Sc. in Economics (University of York). Profesor Titular de Economía Aplicada (en excedencia). Ha publicado en Review of Public Economics IEF, Revista de Economía Aplicada, Journal of Public Administration, Finance and Law, Applied Economic Analysis, Journal of Infrastructure Systems, Papeles de Economía Española, Información Comercial Española, Journal of Insurance and Financial Management etc. Autor entre otros libros de “El papel del gobierno en la era digital” o “DeFi: ilusiones, realidades y desafíos”.