Autor: Ana Patricia Moreno y

Global economic inequality continues to be an unsolved problem as economic resources are not homogeneously spread across the globe. According to the World Bank, more than 700 million people live on less than $2 a day, with half of those extreme poor living in Sub-Saharan Africa.

This daily income entails that the population is completely excluded from the financial system as the payments they need to make are too small for conventional payment networks such as debit and credit cards, where minimum fees make so-called micropayments impossible. This situation is known as financial exclusion1, and is one of th

e elements underlying inequality and poverty worldwide.

Financial exclusion and poverty

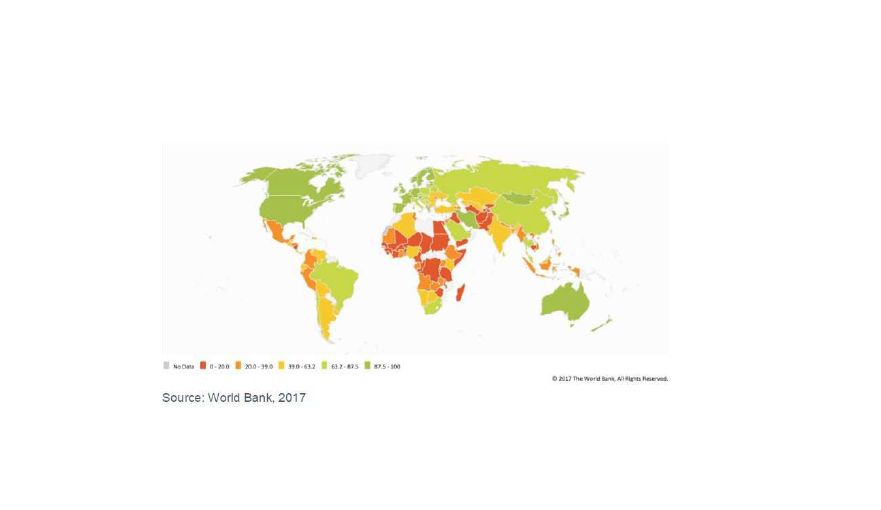

Illustration 1: Levels of financial inclusion

The term financial exclusion refers to the situation of all those agents in society (e.g. individuals, towns) that have no access to the financial system and are not able to have a bank a ccount, to save or to borrow money and are “involuntarily excluded”2 , as shown in Illustration 1:

Financial exclusion is a complex phenomenon linked to several underlying factors, and it is not only present in developing countries, as shown by the fact that in industrialized nations, between 1% and 17% of adults lack a bank account of any kind.

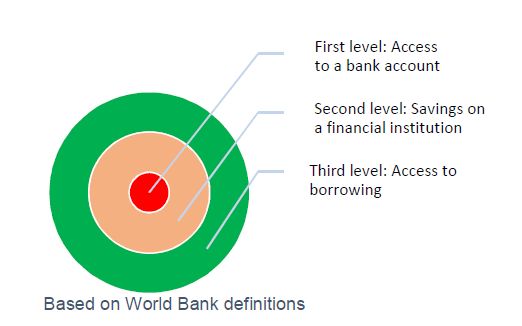

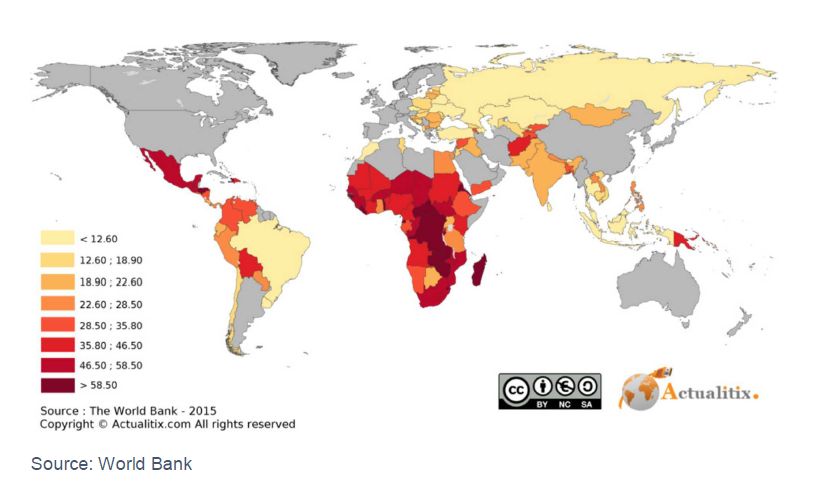

The following maps show how this financial exclusion is present to some extent in every country, but it clearly affects certain regions more severely:

Illustration 2: Percentage of population ( age 15+) with an account in a financial institution

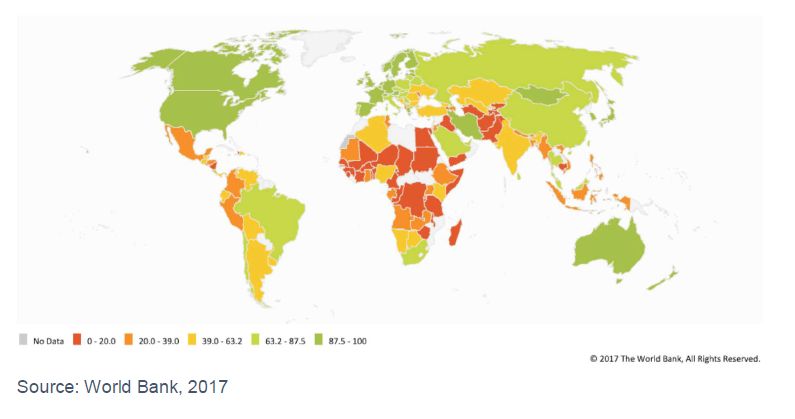

Typically, people on the lowest income brackets are twice as likely to have no bank account as the average, and we can find a prevalence among lone parents, young people (between 18 and 25), students and the unemployed. According to the World Bank, important factors include gender, age, education, income and whether one is living in a city or a country area.

Illustration 3: Age, Education, Income and Residence as factors of financial exclusion

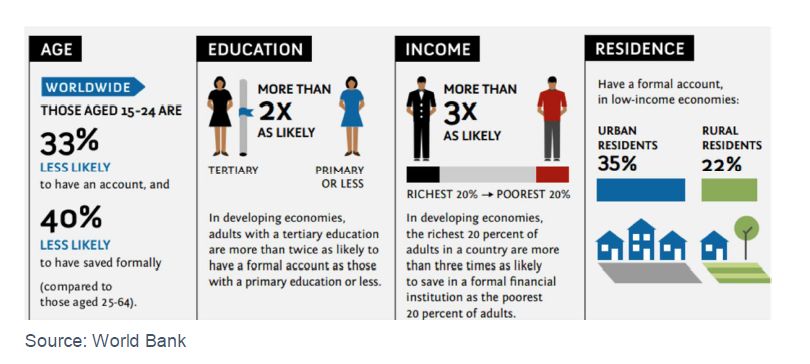

However, despite all this, it is important to note the correlation between financial exclusion and extreme poverty (living under 2$ a day). The following map illustrates the percentage of people living in poverty, and it is easy to observe that those countries with more profound and more widespread financial exclusion are those where poverty is sharper.

Illustration 4: Percentage Of Population Living Below Poverty Line.

In the past, a number of models have tried to reduce financial exclusion, the best-known being microfinance, but recently the focus has shifted from microcredits to promoting financial inclusion, a term that encompasses a far broader range of financial products and providers.

Microfinance: The attempt to reduce poverty

The term microfinance is used to indicate a range of financial services/products involving small amounts offered to low-income/non-bankable customers and micro-enterprises. Microfinance covers a wide range of financial services that include savings, credit, insurance and remittance, targeting those who are not able to obtain credit from formal financial and banking institutions. The theory of how microfinance can reduce poverty is simple: Access to money can give poor people the possibility of being entrepreneurs and starting an activity which could generate a profit. The Nobel Peace Prize Mohammad Yunus was the originator of the term «microfinance» and he defended the claim that the 5% of the population that were helped by microfinance each year managed to move out of poverty.

In practice, it is important to note that some factors limit the efficiency of this system, and despite the initial impression that microfinance could represent a final solution to the problem of poverty, a new debate on this issue has emerged in recent years.

One limitation on the effectiveness of microfinance is the evidence found that the final beneficiaries of the system were those living above the poverty line or people considered “transient poor” instead of the chronic poor people. Those in a situation of chronic poverty are more likely to choose not to establish a business using microcredits since they may have to deal with urgent bills (e.g. medical, funeral) and they are usually more risk-averse and afraid of losing whatever they have, even if it is not a significant amount. Another factor that makes the transient poor more likely to use microcredits is that the interest charged is generally too high for those suffering from extreme poverty.

Also, several studies point to the fact that not all poor people are prepared to develop or maintain a business. Most people do not have the skills, vision, creativity, and persistence to be entrepreneurial. Even in developed countries with high levels of education and access to financial services, about 90 percent of the labor force are employees rather than entrepreneurs. The existence of a sustainable microcredit model, with an adequate entrepreneurial climate and a stable demand that will generate profits for small businesses, is an essential condition to make microfinance more effective. Yunus himself recognized that microfinance is not a final solution to poverty, but can at least mitigate its effects and is more powerful when combined with other actions.

FinTech may solve some of the microfinance problems

FinTech, meaning any financial services provided through technology, is already having an impact on emerging markets ensuring access to financial services and products for the unbanked. The term social FinTech refers to those FinTech tools aimed at solving or at least having a positive impact, on social problems.

Microfinance is not going to be eliminated by new technology but rather there is room for cooperation between the two, technology acting as a booster for microfinance: Technology could help to tackle the inability of businesses to grow with microcredits because of a lack of skills and entrepreneurial vision required to run a business properly. New technologies could make a significant contribution as the NGOs or microcredit operations could introduce mentoring plans to help local people to gain these skills and build an entrepreneurial environment. And, although money is not the only factor driving demand, technology would allow everybody to accumulate some savings in an account which could then be used to consume goods or services offered by the entrepreneur.

A Fintech model of microfinance: Mobile Banking

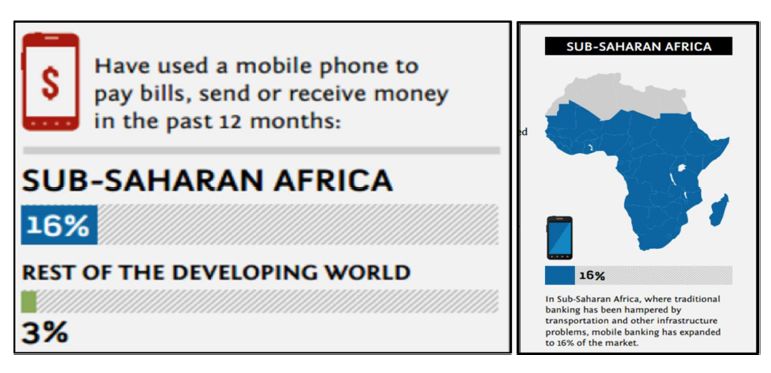

Among the social FinTech possibilities, mobile banking has proved to be very successful in areas such as Sub-Saharan Africa.

One of the factors that favors financial exclusion is the absence of branch banks in specific areas. Mobile banking can provide people with branchless banking, allowing the population to make cash transactions without actually going to a physical branch bank. Mobile savings can be seen as the application of technology to microfinance where lending is the final goal of the process.

Mobile banking is especially interesting and convenient for both the population of underdeveloped countries and banks. Mobile phones are a very inexpensive technology, and so more affordable in areas where establishing a branch bank would not be profitable. In addition to that, mobile phones have a continuous connection to the network and secure user identification, so transactions could be made almost anytime anywhere.

Mobile savings can be classified in two groups: “basic mobile savings” and “bank-integrated mobile services”. The former refers to the storing of electronic money, which could only reach the second level of financial inclusion, while the latter also includes interest and other financial instruments, and could also reach the third level of financial inclusion, such as loans and borrowing.

Drivers of the Success of Mobile Banking in Africa

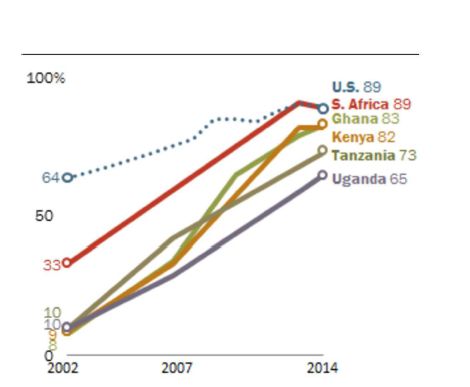

Mobile phones have been one of the biggest innovations of the century, and the adoption of this technology had been one of the fastest in history. While in many African countries water or food are almost luxury services, the percentage of adults owning a cell phone is near to that of the US, as can be seen in Illustration 5:

Illustration 5: Percentage of Adults owning a cell phone

This expansion in the number of mobile phones led to banks recognizing the potential of reaching millions of prospective customers, especially the rural population, who account for more than 60% of Africa’s total population and have no access to banking services. The lack of bank branches is a clear catalyst for mobile banking, while in the developed world, where financial institutions are physically present everywhere, mobile phones are not being used as intensively as in Africa for financial purposes.

Illustration 6: Comparison of mobile banking services between Africa and developed countries

In the last decade some really successful stories have pioneered the pathway for mobile banking for the financial excluded, M-Pesa in Kenya being probably the best known of all. M-Pesa was launched in 2007 by Safaricom (the African subsidiary of Vodafone). It was intended to be a financial service targeting the unbanked population. M stands for mobile, and Pesa stands for money in Swahili.

The service was an e-wallet connected to the user’s mobile account that could be accessed through the SIM card. Initially, only peer to peer transfers were possible, but the evolution and success of M-Pesa also included peer to business and international transfers. M-Pesa does not require immediate payments or withdrawals because e-money can be accumulated over time, so it also works as a savings instrument. A text message (SMS) is issued to the customer’s phone after each transaction. This instant recording protect the users and allows them to keep a record of payments. Additionally, the accounts are supported with a 24/7 service provided by Safaricom and the Vodafone Group.

The initial business plan did not anticipate the incredible success of the venture. In the first month alone, more than 20,000 customers signed up for the service, it is now used by 1.7 million people and recent estimates suggest that around 25% of the country’s gross national product flows through the system. One of the factors in the scheme’s success was that a bank account was not a prerequisite for registering; one simply had to be a Safaricom customer and to own a national ID card.

Mobile Money for the Unbanked is an organization set up by the GSM Association3 that specializes in monitoring and advising about mobile banking and its impact on financial exclusion. It estimates that around 80 services similar to M-Pesa are now in operation around the world.

If financial exclusion has been identified as one of the factors underlying extreme poverty, it is important to ensure that people are able to access the financial system in order to fight chronic poverty. The fast implementation of technologies in underdeveloped countries makes mobile banking, among other Social Fin Tech solutions, a relevant tool to boost financial inclusion, bringing financial solutions for those who are excluded and could hardly access it any other way.

“Financial inclusion helps lift people out of poverty and can help speed economic development. It can draw more women into the mainstream of economic activity, harnessing their contributions to society” Sri Mulyani Indrawati, Indonesian Minister of Finance and former COO of World Bank

1 According to the G20, 2.5 billion adults are excluded from the formal financial system.

2 It doesn´t include those “voluntarily excluded”, meaning people who have access to banks but do not wish to use their services.

3 Representing mobile phone operators, regulators and others

Autor:

Ana Patricia Moreno es graduada en Ingeniería de Telecomunicaciones por la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid y Máster en Ingeniería de Telecomunicaciones y MBA por la Universidad Pontificia de Comillas. Desde enero de 2017 trabaja como Iberia Trade Analyst en Procter and Gambl. Durante este periodo cursó un módulo de Data Science en el MIOTI (Madrid Institute Internet of Things). Colabora con distintas ONGs, entre ellas la Fundación Pablo Horstmann con la que viajó a África en 2016.

Rocío Sáenz-Diez es profesora desde 2003 del departamento de Gestión Financiera en la Universidad Pontificia Comillas de Madrid, donde se licenció en Derecho y ADE (especialidad E-3). Trabajó unos años como profesional en el sector financiero, tanto en Londres (Corporate Finance Merrill Lynch) como en Madrid (Equity Research UBS). Posteriormente se incorporó a la universidad defendiendo la tesis doctoral en 2004.