Autor: Carlos Contreras

Over the last decades, we have witnessed the emergence of the theory of behavioural finance, which has meant the addition of new approaches to the studies on financial markets.

By recognizing the role of human behaviour behind price movements, this theory emphasizes the need to include human elements such as loss aversion, overconfidence, over and under-reaction or anchoring in financial studies. One specific case of this relates to herding, nowadays widely believed to be an important feature of financial markets. Since seminal work on the subject, a growing literature has accumulated on theoretical explanations. After the financial crises of the 1990s, many scholars suggested that herd behaviour might be a reason for excess price volatility and the fragility of financial systems. The contagion effects observed during the financial crisis of 2007 have vigorously pushed again this area of investigation.

Some questions that have been addressed in the literature on theoretical analysis of herd behaviour in financial markets include the following:

i. What actions can be qualified as herding in financial markets?

ii. Who engages herd behaviour?

iii. Why do market participants herd?

iv. Can herding be a rational behaviour?

v. May herding behaviour jeopardize social welfare?

We try to answer some of these questions in this brief note.

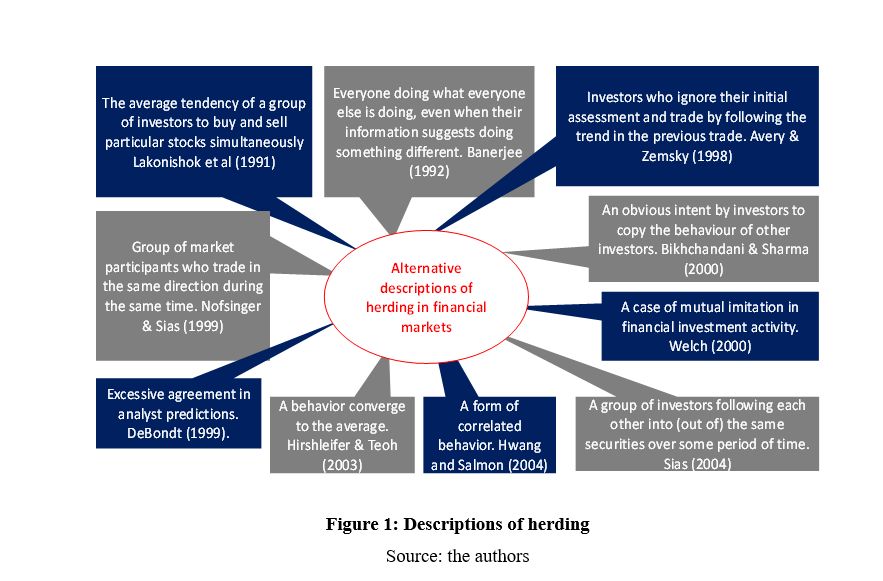

The notion of herding in financial markets relates to the possibility that agents choose the same action independently of their private information. The concept of herding has been expressed in a number of ways. See figure 1 for alternative descriptions.

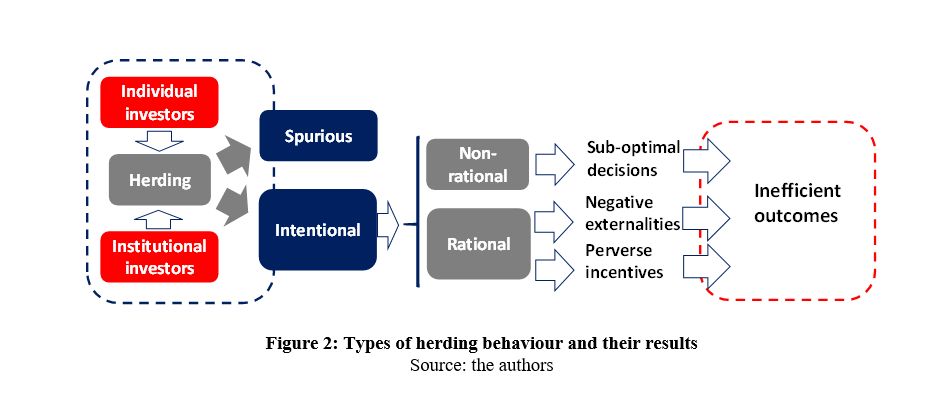

In financial markets, participants sometimes react to the same piece of information (related to a change in financial fundamentals) in a similar way. Reacting to commonly known public information arrival (or correlated private information) by adopting similar investment decisions has been called spurious herding. Spurious herding may also arise in scenarios of differences in investment opportunities due to legal restrictions. This type of fundamentals-driven herding may result in efficient outcomes.

By contrast, intentional herding occurs when agents make decisions based solely on the actions of other agents, foregoing their own private information. Intentional herding may take place at both the individual investor level and at the institutional investor (and analyst) level.

Moreover, both type of investors (individual and institutional) may behave in a rational or in an irrational way. Imitative behaviour associated with herding has often been viewed as the product of irrational decision-making. See figure 1.

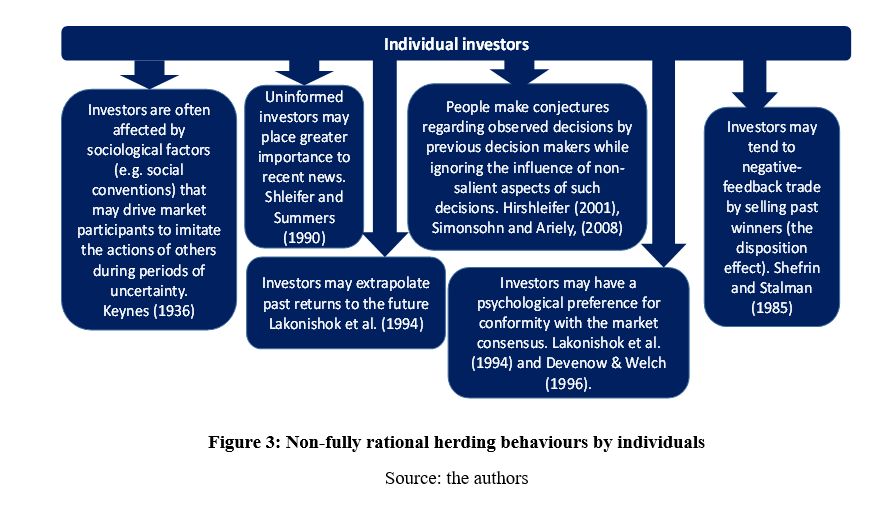

In this context, a number of circumstances have been identified in which individual market participants may show non-fully rational herding behaviour. (See Table 2).

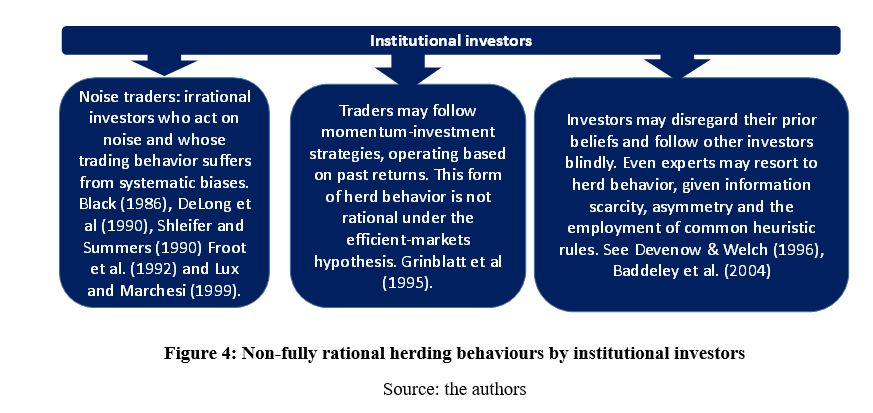

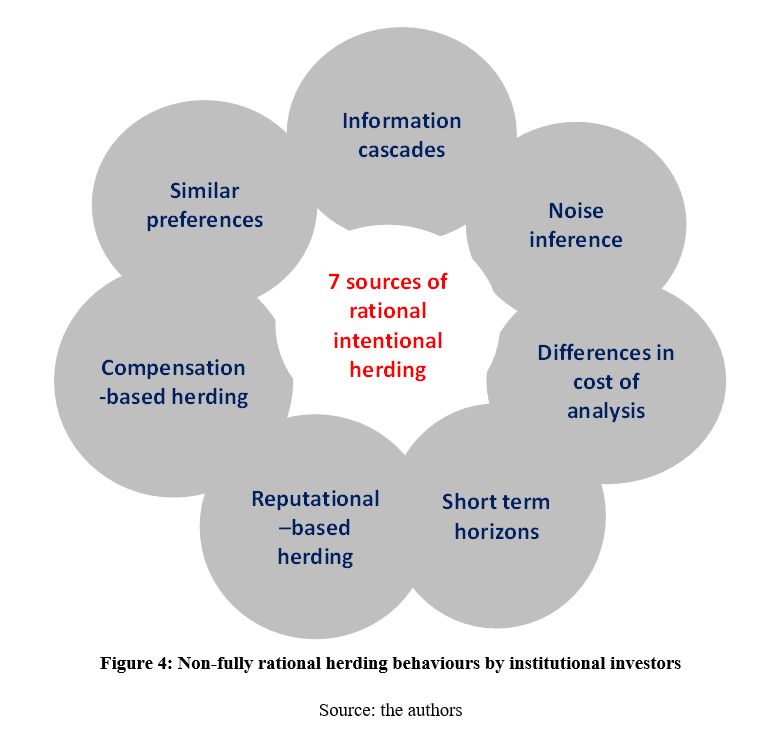

Nevertheless, not only individuals may behave irrationally. Institutional market participants may also behave in a non-fully rational way in several circumstances. See figure 4.

However, herding may also be a rational behaviour in a utility-maximising sense. In economic and financial environments in which decision makers have imperfect information about the true state of the world, it can be rational to ignore one’s own private information and make decisions based upon what are believed to be more informative public signals. In financial markets, agents may observe private signals and make public decisions. At least seven sources of rational intentional herding have been acknowledged in the literature. See figure 5.

An informational cascade (Bikhchandani et al., 1992) is said to occur when it becomes rational to ignore one’s own private information and instead follow the predecessors’ decisions. In a sequential decision model where investment decisions are not taken at the same time, investors face informational differences. When investors have private information, herd behaviour is rational when it is thought that other participants in the market are better informed and their actions reveal this information. This investor may revise his beliefs generating a snowballing effect.

A second source of rational herding relates to noise inference. There is uncertainty as to the average accuracy of traders’ information so that market participants hold mistaken but rational beliefs that most traders’ possess very accurate information. Sometimes herding may occur when investors have a common piece of information that market makers do not have. This noisier inference leads market-makers to update their beliefs more slowly than investors (Avery and Zemsky, 1988).

A third source of rational herding behaviour is linked to differences in the cost of analysis. Less sophisticated investors who mimic popular financial gurus or follow the activities of successful investors behave rationally, since using their own information/knowledge would incur a higher cost. If the cost of the information about the predecessors’ actions is very expensive then all the agents will act according to their own signals, but when observing is free one engages in herd behaviour (Khan, Hassairi and Viviani, 2011).

An alternative type of intentional herding that can be rational arises from considering short-term horizons. Herding can be a rational choice if investors do not have long enough horizons. If speculators have short horizons they may herd on the same information trying to learn, what other informed investors also know.

Additionally, herding behaviours may be explained by the role of reputation. Asset managers and financial analysts may herd because of career and reputational concerns. Reputation and probability of being fired may lead to herd behaviour in order to protect themselves from underperformance. Then, herding can be seen as insurance against underperformance. See Friedman (1984), Scharfstein et al. (1990) and Rajan (2006). In the same vein, compensation methods in financial institutions may turn into herding. In a context of asymmetric information, compensation schemes in which payoff to asset managers (i.e. the agents) increases with their own performance and decreases with underperforming the benchmark cause the agents to skew their investments towards the benchmark portfolio. See Maug and Naik (1995) and Admati and Pfleider (1997).

Finally, herd behaviour sometimes occurs because investors share similar preferences. Institutional investors are averse to stocks with lower liquidity or that have high transaction costs.

On the other hand, there is consensus regarding the fact that non-rational intentional herd behaviour can lead to sub-optimal decisions, creating inefficient outcomes. However, economists have also proven that rational behaviour (although efficient on an individual basis) may be socially inefficient. This negative outcome may arise in the presence of negative externalities as well as when rational agents have incentives to manipulate the environment of early decision makers.

Autores:

Carlos Contreras. MSc in Economics (University of York), PhD in Economics (Universidad Complutense de Madrid). Associate Professor of Applied Economics (UCM). His research has been published in journals such as Review of Public Economics IEF, Revista de Economía Aplicada, Journal of Public Administration, Finance and Law, Journal of Infrastructure Systems, Papeles de Economía Española and others.

Alvaro Contreras: BSc Economics and Finance Graduate from University of Bristol and MSc Finance Candidate at Imperial College London.